📅 Last updated: March 9, 2025

🎃 Welcome to The Coder Cafe! Today, we examine the Therac-25 accidents, where design and software failures resulted in multiple radiation overdoses and deaths. Make sure to check the Explore Further section to see if you’re able to reproduce the deadly issue. Get cozy, grab a pumpkin spice latte, and let’s begin!

Therac-25

Treating cancers used to require a mix of machines, depending on tumor depth: shallow or deep. In the early 1980s, a new generation promised both from a single system. That was a big deal for hospitals: one machine instead of several meant lower maintenance and fewer systems to manage.

That was the case with the Therac-25.

The Therac-25 offered two therapies with selectable modes:

Electron beam: Low-energy electrons for shallow tumors (e.g., skin cancer).

X-ray photons: High-energy radiation for deep tumors (e.g., lung cancer).

Earlier Therac models allowed switching modes with hardware circuits and physical interlocks. The new version was smaller, cheaper, and computer-controlled. Less hardware and fewer parts meant lower costs.

However, what no one realized soon enough: it also removed an independent safety net.

The Horror Begins

On a routine day, a radiology technologist sat at the console and began entering a plan:

By habit, she selected X-ray (deep mode).

Then she immediately corrected it for Electron (shallow mode) and hit start.

The machine halted with a MALFUNCTION 54 message. The operator’s manual didn’t explain the code. Service materials listed the number but gave no useful guidance, so she resumed and triggered the radiation.

The patient was receiving his ninth treatment. Immediately, he knew something was different. He reported a buzzing sound, later recognized as the accelerator pouring out radiation at maximum. The pain came fast; paralysis followed. He later died from radiation injury.

Weeks later, a second patient endured the same incident on the same model.

What Happened?

Initially, the radiology technologist entered ‘X’ for X-ray (‘▮’ is the cursor and ‘…’ are other fields):

MODE: X

... ▮

BEAM READY: She immediately hit Cursor Up to go back and correct the field to ‘E’:

MODE: E

... ▮

BEAM READY: After a rapid sequence of Return presses, she moved back down to the command area:

MODE: E

...

BEAM READY: ▮From her perspective, the screen showed the corrected mode, so she hit return and started the treatment:

MODE: E

...

BEAM READY: ▮<Enter>Behind the scenes, the Therac-25 software ran several concurrent tasks:

Data-entry task: Monitored operator inputs and edited a shared treatment-setup structure.

Hardware-control task: On a periodic loop, snapshotted that same structure and positioned the turntable and magnets based on user input.

Because both tasks read the same memory with no mutual exclusion, there was a short window (on the order of seconds) in which the hardware-control task used a different value than the one displayed on the screen.

As a result:

The UI showed Electron mode, which looked correct to the operator.

The hardware-control task had snapshotted stale data and marked the system as ready even though critical elements (e.g., turntable position, scanning magnets/accessories) were not yet aligned with electron mode.

When treatment was started, the machine delivered an effectively unscanned, high-intensity electron beam, causing a massive overdose.

This is a race condition example: the outcome depends on the timing of events, here, the input cadence of the technologist. Depending on the timing, the system could enter a fatal state, with one process seeing ‘X’ while another saw ‘E’.

The manufacturer later confirmed the error could not be reproduced reliably in testing. The timing had to line up just right, which made the bug elusive. They initially misdiagnosed it as a hardware fault and applied only minor fixes. Unfortunately, the speed of operator editing was the key trigger that exposed this software race.

Another Tragedy

The problem could have stopped here, but it didn’t.

Months later, another fatal overdose occurred, this time caused by a different software defect. It wasn’t a timing race. This time, the issue was a counter overflow within the control program.

The software used an internal counter to track how many times certain setup operations ran. After the counter exceeded its maximum value, it wrapped back to zero. That arithmetic overflow created a window where a critical safety check was bypassed, allowing the beam to turn on without the proper accessories in place.

Again, the Therac-25 fired a high-intensity beam without the proper hardware configuration.

Conclusion

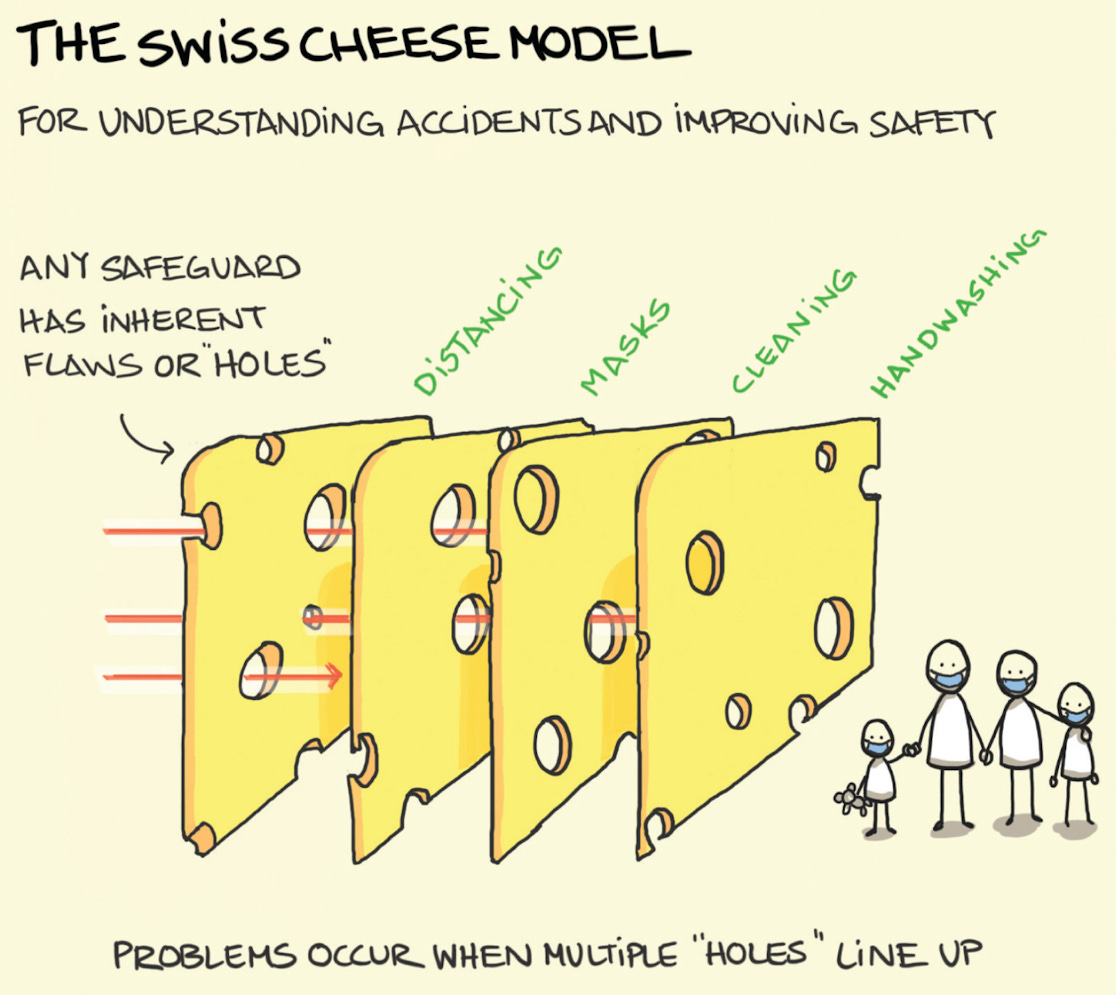

Both the race condition and the counter overflow stemmed from the same design flaw: the belief that software alone could enforce safety. The Therac-25 showed, in tragic terms, that without independent safeguards, small coding errors can have catastrophic consequences.

We should know that whether it’s software, hardware, or a human process, every single safeguard has inherent flaws. Therefore, in complex systems, safety should be layered, as illustrated by the Swiss cheese model:

In total, there were six known radiation overdoses involving the Therac-25, and at least three were fatal.

Resources

More From the Reliability Category

Sources

Explore Further

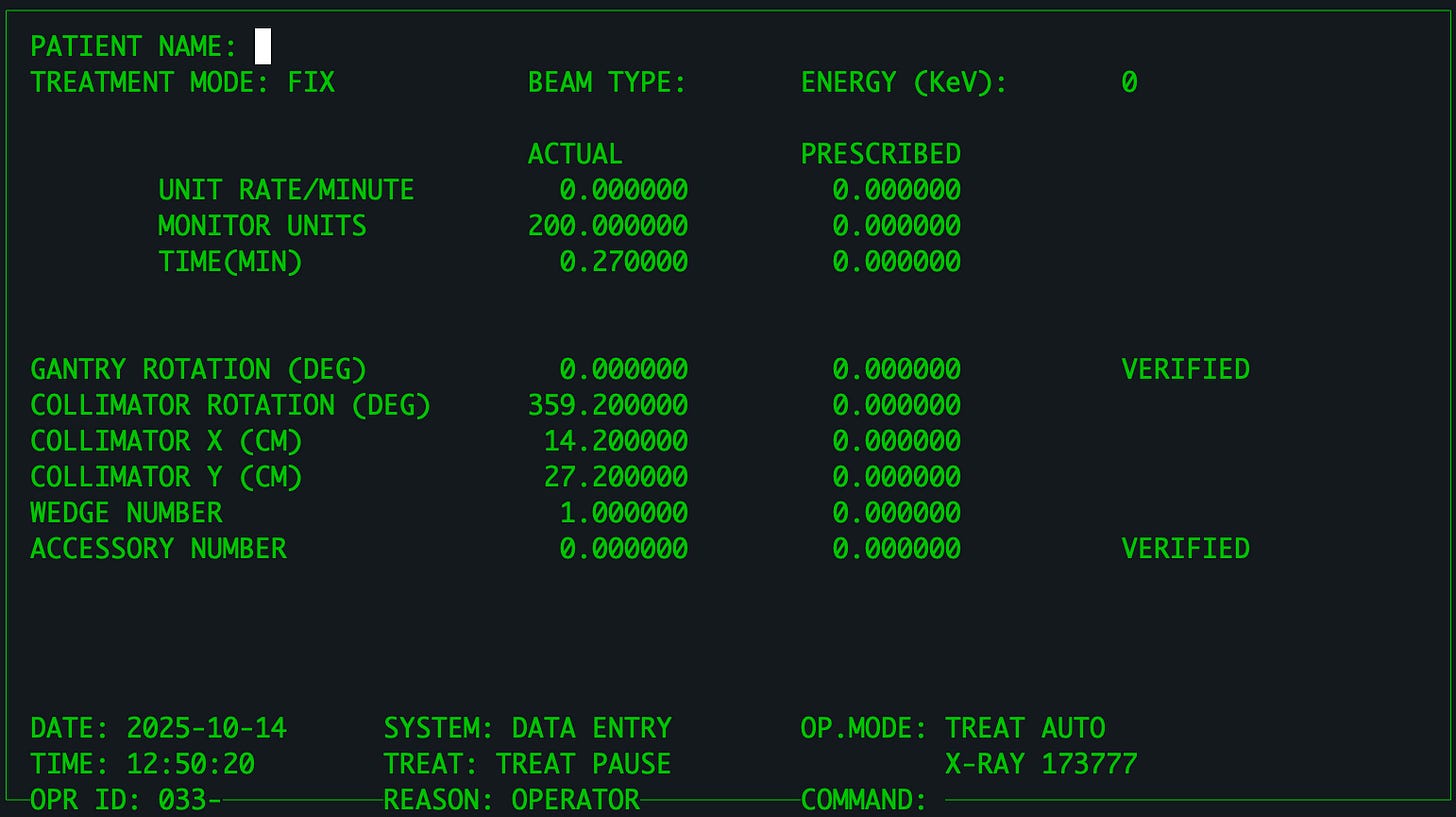

I created a Docker image based on a C implementation from an MIT course simulating the operator console of the Therac-25 interface:

You can run the UI using Docker:

docker run --rm -it -e TERM=xterm-256color teivah/therac-25Simulator commands:

Beam Type: ‘

X’ or ‘E’Command: ‘

B’ for beam on, or ‘Q’ to quit the simulator.

👉 Try to trigger the MALFUNCTION 54 error based on the scenario discussed.

❤️ If you enjoyed this post, please hit the like button.

💬 Any other horror coding stories you want to share?